Peripheral Territories and the Built Heritage as a Cultural, Social and Economic Differentiation

Resource – brief approach to the case of the Portuguese/ Spanish Border Line Fortifications

MSc Spatial Planning and Development Policies

The pace of change and the social, economic and cultural evolution imposed by globalization is one of the most important trends that we face today. In all regions, the social and economic evolution and population density changes make their management increasingly complex.

The on-going process of globalization determines that small and peripheral regions must “gather its roots” and look for its own and endogenous values to face that process and the most powerful regions and groups that are controlling it, in order to make a stand in the modern globalized world.

According to John Friedmann (Friedmann, 1996[i]), economic policies guided by dominant economic thinking generally tend not to consider the interests of the most deprived or disadvantaged groups, which means the interests of the peripheral regions and its people. He proposes an alternative approach to development that is more inclusive, based on a policy of empowering local groups of actors. He refers that if we are dealing with a question or a local problem, it is easier to promote the mobilization of civil society.

Nevertheless, uncertainty about the future, even the nearest one, is getting higher, because present territories are constantly changing at an increasingly high rate. The globalizing nature of that change tends to limit the importance of local resources and, on the other hand, to strengthen them as important landmarks of differentiation and cultural identification. This means that innovative and inclusive strategies are important, based on the binomial relation competitiveness/ complementarity between regions, aiming the potential of its own attributes.

On the question of the use of local resources, Albert Hirschman (Hirschman, 1958[ii]), went beyond the dominant idea of the need for development factors normally considered, such as capital, education, and business dynamics. Hirschman said that the resources normally exist, although they are not visible or used and the most important factor to create the desired economic development is a “basic organizational capacity”. Thus, the real problem is to find, interconnect and unite resources (existing and latent) in order to build community development, considering it as a collective social goal. In his perception of development, Hirschman says that it does not depend so much on the optimal combination of existing resources and factors of production, but rather on the ability to consider the resources and skills that may be hidden, dispersed or misused.

This means that local and regional cultures (values, traditions, gastronomy, patrimony, built heritage) are crucial for the future of the people living within those regions, especially the low density areas, in order to increase their sense of belonging, their solidarity and cohesion efforts and therefore, increase their social capital and their institutional capacity and minimize globalization’s eventual negative impacts, many times related with economic externalities. Therefore, local and regional authorities must be genuinely concerned about the use of endogenous resources, both natural and human, productive and patrimonial.

Considering the idea of “hidden, dispersed or misused” resources, a path was started in Portugal, about a decade ago, to consider the importance of the fortifications of the Portuguese-Spanish border line (“Raia”), as a whole in which those places could “enlighten” their future creating a unique route in the world, through the stars formed by the bulwarked ones.

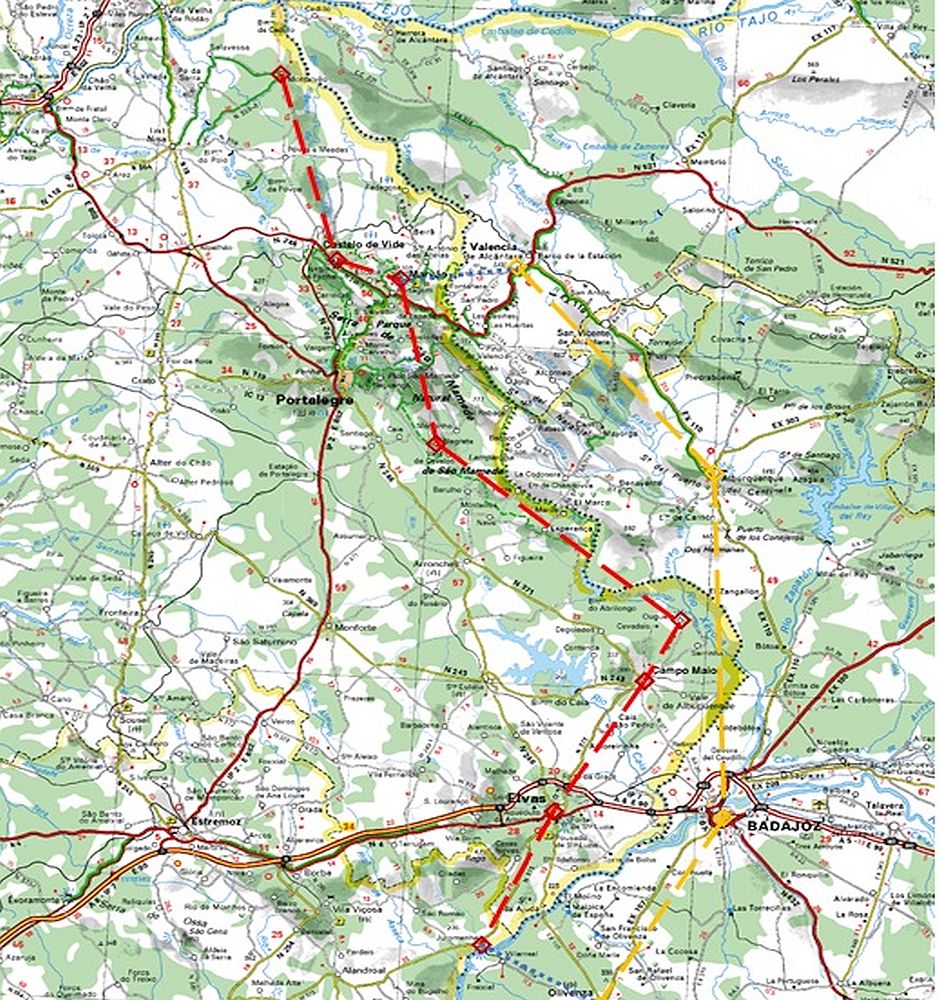

In 2009, the Centro de Estudos de Arquitectura e Urbanismo of the Faculdade de Arquitectura of the University of Porto, in a program of studies about the line of frontier between Portugal and Spain, in the Region of Alentejo (and Extremadura, on the Spanish side), made a prospection study in which the basic aim was to identify the “invisible values”[iii] that could be valorized to improve the conditions of sustainability in those territories. In fact, a route of the Fortifications along the border was defined, considering the connection between places like, from North to South, Montalvão, Castelo de Vide, Marvão, Alegrete, Ouguela, Campo Maior, Elvas and Juromenha. On the other side of the border (in Spain) we had Valencia de Alcántara, Albuquerque, Badajoz and Olivenza. The connections between the two sides could be made linking Marvão to Valencia de Alcántara (Northern Connection) and Juromenha to Olivenza (Southern Connection). This way, we could have an international route that would strengthen the ties between those populations, foster the conservation of the monuments and bring an important upgrade in the tourism for these regions, allowing its people to show their costumes and their manners and expanding its commercial potential, namely in the craftwork.

The importance of this path considers the idea that heritage policies in the last century are (or at least should be) based on the assumption that the collective identity of a People is closely linked to its built patrimony heritage. Castles, cathedrals, fortifications, churches and other buildings of erudite, historical or unique architecture are the built testimony of the History of the Country and its people, considering that within its walls some very important historical events took place over the centuries, many of them crucial in the History of the Country.

In fact, Portuguese Cultural Heritage Basic Law promotes the enhancement of cultural heritage, “as a reality of the greatest relevance for the understanding, permanence and construction of the national identity and for the democratization of culture”, in order to “ensure the transmission of a national heritage whose continuity and enrichment will unite the generations in a singular civilizational journey”.

So, this path culminated with the recent candidacy of the bulwarked Fortifications of the Portuguese/ Spanish border line (“Raia”), recently promoted by the municipalities of Almeida, Elvas, Marvão and Valença, which is already registered in the UNESCO Indicative List of Portugal, towards its classification as World Heritage.

The four municipalities developed a joint application, based on the work carried out by each of them and with the scientific support of several entities, considering that the achievement of the UNESCO award will bring great advantages to this territory and to Portugal, also enriching the list of places already classified as World Heritage.

Mayors of the four municipalities referred “the high cultural interest that represents for the Country and for Humanity the future international recognition of a unique heritage in the context of European civilization” as “unique examples of the military architecture of the 17th and 18th centuries, along with the intangible value of Peace and the relationship between People” confirming the idea that this will be “a strong attraction for tourists”.

The bulwarked fortifications are defensive structures of war, mainly from the 17th and 18th centuries. Considering that they are unique spaces of history, culture and human relations and experiences, they became what some call “monuments of peace”. Its architectural models reflect innovation and unique solutions in its construction years, adapted to walled structures, built in the course of ages, and to the geomorphology of the terrain.

This defensive system of the bulwarked fortifications is truly important, considering it is located within one of the oldest border lines in the world. It is unique in the world, with exceptional characteristics which can foster the conservation of this patrimonial legacy and promote culture and tourism and therefore people’s sense of belonging and regional cohesion.

Known results of these kind of actions show us that it will shape the future of these populations. These policies and strategies will increase Tourism in deprived regions to levels never seen before and all the actions taken to restore, show and defend local heritage, patrimony and manners will bring a new hope for its people. We can, then, conclude that, from this point of view, own and endogenous resources (which, sometimes, may be “hidden” or “invisible” as they are not officially recognized) are the key to the development of these territories and for the future of its people.

[i] FRIEDMANN, J. (1996), “Rethinking Poverty: Empowerment and Citizen Rights”, International Social Sciences Journal, UNESCO, Nº148: 161-172.

[ii] HIRSCHMAN, Albert O. (1958), “The Strategy of Economic Development”, New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

[iii] As invisible values we considered all the elements of the territory (material and non-material) that are part of the local culture but not recognized by official statistics because of their usually small dimension or expression (namely local wine or other products of local know-how) or because of its immaterial characteristics (such as local ceremonies and festivities, containing lots of symbolism that link the people to the territory).

Cover Image

Elvas:

http://elvasnews.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Planta-da-cidade-de-Elvas.jpg

Accompanying images

1. Forte de Nossa Senhora da Graça/ Forte de Lippe:

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/Dd60jO1kF1U/maxresdefault.jpg

2. Marvão:

https://www.visitportugal.com/sites/www.visitportugal.com/files/styles/destinos_galeria/public/mediateca/N24031.jpg?itok=VHhnTkAy

3. Rota das Fortalezas da Raia Alentejana (Nuno Bigotte Santos)